Accessibility tooling and assistive technology

Next, we turn our attention to accessibility tooling, providing information on the kinds of tools you can use to help solve accessibility issues, and helping you understand the assistive technologies used by people with disabilities to help them browse the web. You'll be using the tools described here throughout subsequent articles.

| Prerequisites: | Familiarity with HTML, CSS, a basic understanding of accessibility concepts. |

|---|---|

| Learning outcomes: |

|

Accessibility tools

Let's have a look at the tools and techniques you can use for testing website accessibility and fixing the issues you uncover.

Testing source order

Your content should make logical sense in its source order — you can always display it differently with CSS later on, but you should get the underlying structure correct to begin with. This is because assistive technologies read website content based on the order of the source, and disabled people often modify or turn off parts of the CSS to make content more legible (common examples are increasing font size and applying high contrast color schemes).

To test source order, you can turn off a site's CSS and see how understandable it is without it. You could do this manually by just removing the CSS from your code, but the easiest way is to use browser features, for example:

- Firefox: Select View > Page Style > No Style from the main menu.

- Safari: Open the browser developer tools, click the Device Settings button near the top-left of the developer tools panel (looks like a computer monitor), then check the "Disable CSS" checkbox in the panel that appears.

- Chrome/Edge: Install the Web Developer Toolbar extension, then restart the browser. Click the "Web Developer" gear icon that should now be available in your extensions menu, then select CSS > Disable All Styles.

Color contrast checkers

When choosing a color scheme for your website, you should make sure that the text (foreground) color contrasts well with the background color. Your design might look cool, but it is no good if people can't read your content. Use a tool like WebAIM's Color Contrast Checker to check whether your scheme is contrasting enough.

Another tip is to avoid using only color for signposts or highlighting important information, as this might be missed by people with visual impairments like color blindness. Instead of marking required form fields in red, for example, mark them with an asterisk and in red.

Note: A high contrast ratio will also allow anyone using a smartphone or tablet with a glossy screen to better read pages when in a bright environment, such as sunlight.

Auditing tools

There are several auditing tools available that you can feed your web pages into. They will look over them and return a list of accessibility issues present on the page. Let's look at Wave as an example, an online accessibility testing tool that accepts a web address and returns an annotated view of that page with accessibility problems highlighted.

- Go to the Wave homepage.

- Enter the URL of our bad-form.html example into the text input box near the top of the page. Then press enter or click/tap the arrow at the far right edge of the input box.

- The site should highlight the accessibility problems present. Click the displayed icons to see more information about each of the issues identified by Wave's evaluation.

Other auditing tools that are worth checking out:

Note: Such tools aren't good enough to solve all your accessibility problems on their own. You'll need a combination of these, knowledge and experience, user testing, etc. to get a full picture.

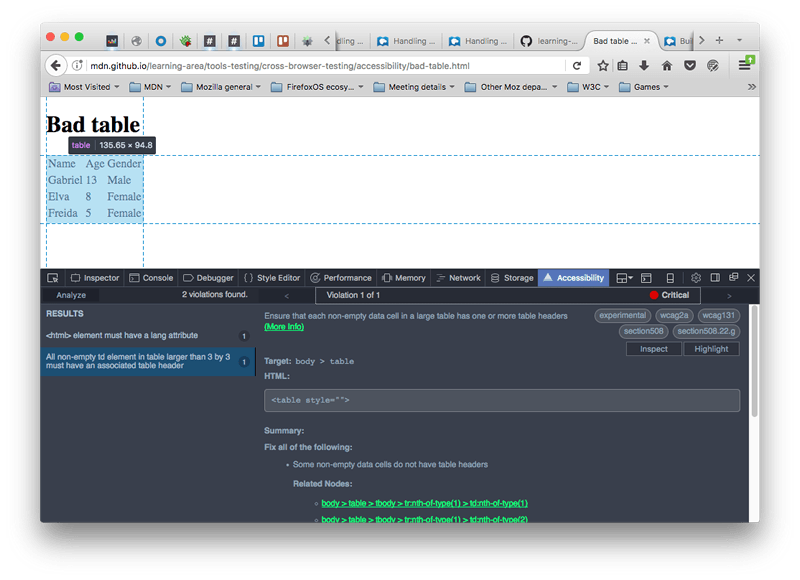

Deque's aXe tool goes a bit further than the auditing tools we mentioned above. Like the others, it checks pages and returns accessibility errors. Its most immediately useful form is probably the browser extensions:

These add an accessibility tab to the browser developer tools. For example, we installed the Firefox version, then used it to audit our bad-table.html example. We got the following results:

aXe is also installable using npm, and can be integrated with task runners like Grunt and Gulp, automation frameworks like Selenium and Cucumber, unit testing frameworks like Jasmine, and more besides (again, see the main aXe page for details).

Screen readers

One of the most common types of assistive technology (AT) that disabled people use — and one of the most common ones you'll use to test the accessibility of your webpages — is screen readers. These are pieces of software that read out webpage content or content from other apps installed on someone's operating system. Screen readers enable people to use computers without having to see any visual content.

Web browsers expose information about the page's content for screen readers (and other AT) to communicate to the user through a representation called the accessibility tree. This provides semantic information such as names and descriptions of elements, what their purpose or role is (is it a button, or an input field?), and whether they are in a particular state (for example, is a dialog box open or closed?).

This information might be trivial in the case of a paragraph of text, which sounds pretty much how it is written, but it can get complicated when it comes to user interface features such as a drop-down menu or a video player. This is why it's very important to use semantic HTML correctly, which you'll look at in detail in the next article in this module. If you mark up content using the wrong element, it can confuse screen reader users.

Make sure you have a screen reader or two installed on your development machine, and try using your favorite websites via a screen reader, as discussed below. Understanding how visually impaired people use the web is key to designing products that work better for everyone.

What screen readers are available?

There are several screen readers available:

- Some are paid-for commercial products, like JAWS (Windows).

- Some are free products, like NVDA (Windows), ChromeVox (Chrome, Windows, and macOS), and Orca (Linux).

- Some are built into the operating system, like VoiceOver (macOS and iOS), ChromeVox (on Chromebooks), and TalkBack (Android).

Generally, screen readers are separate apps that run on the host operating system and can read web pages and content in other apps as well (this is not always the case; ChromeVox for example is a browser extension). Screen readers tend to have some differences in exact behavior and controls, so you'll have to consult the documentation for your chosen screen reader to get all the details. Saying that, they all work in basically the same sort of way.

In the next couple of sections, we'll go through some tests with a couple of different screen readers to give you a general idea of how they work and how to test with them.

Note: WebAIM's Designing for Screen Reader Compatibility provides some useful information about screen reader usage and what works best for screen readers. Also see Screen Reader User Survey #10 Results for some interesting screen reader usage statistics.

VoiceOver

VoiceOver (VO) comes free with Apple mac/iPhone/iPad, so it's useful for testing on desktop/mobile if you use Apple products. We tested it on macOS on a MacBook Pro.

To turn it on, press Cmd + F5. If you've not used VO before, you will be given a welcome screen where you can choose to start VO or not, and run through a rather useful tutorial to learn how to use it. To turn it off, press Cmd + F5 again.

Note: You should go through the tutorial at least once — it is a really useful way to learn VO.

When VO is on, the display will look mostly the same, but you'll see a black box at the bottom left of the screen that contains information on what VO currently has selected. The current selection will also be highlighted, with a black border — this highlight is known as the VO cursor.

To use VO, you will make a lot of use of the "VO modifier" — this is a key or key combination that you need to press in addition to the actual VO keyboard shortcuts to get them to work. Using a modifier like this is common with screen readers, to enable them to keep their commands from clashing with other commands. In the case of VO, the modifier can either be CapsLock, or Ctrl + Option.

VO has many keyboard commands, and we won't list them all here. The basic ones you'll need for web page testing are in the following table. In the keyboard shortcuts, "VO" means "the VoiceOver modifier".

| Keyboard shortcut | Description |

|---|---|

| VO + Cursor keys | Move the VO cursor up, right, down, left. |

| VO + Spacebar | Select/activate items highlighted by the VO cursor. This includes items selected in the Rotor (see below). |

| VO + Shift + down cursor | Move into a group of items such as an HTML table or form. Once inside a group, you can move around and select items inside that group using the above commands as normal. |

| VO + Shift + up cursor | Move out of a group. |

| VO + C | (when inside a table) Read the header of the current column. |

| VO + R | (when inside a table) Read the header of the current row. |

| VO + C + C (two Cs in succession) | (when inside a table) Read the entire current column, including header. |

| VO + R + R (two Rs in succession) | (when inside a table) Read the entire current row, including the headers that correspond to each cell. |

| VO + left cursor, VO + right cursor | (when inside some horizontal options, such as a date picker) Move between options. |

| VO + up cursor, VO + down cursor | (when inside some horizontal options, such as a date picker) Change the current option. |

| VO + U | Open the Rotor, which displays lists of headings, links, form controls, etc. for easy navigation. |

| VO + left cursor, VO + right cursor | (when inside Rotor) Move between different lists available in the Rotor. |

| VO + up cursor, VO + down cursor | (when inside Rotor) Move between different items in the current Rotor list. |

| Esc | (when inside Rotor) Exit Rotor. |

| Ctrl | (when VO is speaking) Pause/Resume speech. |

| VO + Z | Restart the last bit of speech. |

| VO + D | Go into the mac's Dock, so you can select apps to run inside it. |

This seems like a lot of commands, but it isn't so bad when you get used to it, and VO regularly gives you reminders of what commands to use in certain places. Have a play with VO now; you can then go on to play with some of our examples in the Screen reader testing section.

NVDA

NVDA is Windows-only, and you'll need to install it.

- Download NVDA from nvaccess.org, then install it. You can choose whether to make a donation or download it for free; you'll also need to give them your email address before you can download it.

- To start NVDA once installed, double-click on the program file/shortcut, or use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + Alt + N. You'll see the NVDA welcome dialog when you start it. Here you can choose from a couple of options, then press the OK button to get going.

NVDA will now be active on your computer.

To use NVDA, you will make a lot of use of the "NVDA modifier" — the key that you need to press in addition to the actual NVDA keyboard shortcuts to get them to work. The NVDA modifier can either be Insert (the default), or CapsLock (can be chosen by checking the first checkbox in the NVDA welcome dialog before pressing OK).

Note: NVDA is more subtle than VoiceOver in terms of how it highlights where it is and what it is doing. When you are scrolling through headings, lists, etc., items you are selected on will generally be highlighted with a subtle outline, but this is not always the case for all things. If you get completely lost, you can press Ctrl + F5 to refresh the current page and begin from the top again.

NVDA has many keyboard commands, and we won't list them all here. The basic ones you'll need for web page testing are in the following table. In the keyboard shortcuts, "NVDA" means "the NVDA modifier".

| Keyboard shortcut | Description |

|---|---|

| NVDA + Q | Turn NVDA off again after you've started it. |

| NVDA + up cursor | Read the current line. |

| NVDA + down cursor | Start reading at the current position. |

| Up cursor and down cursor, or Shift + Tab and Tab | Move to the previous/next item on page and read it. |

| Left cursor and right cursor | Move to the previous/next character in current item and read it. |

| Shift + H and H | Move to the previous/next heading and read it. |

| Shift + K and K | Move to the previous/next link and read it. |

| Shift + D and D |

Move to the previous/next document landmark (e.g., <nav>)

and read it.

|

| Shift + 1–6 and 1–6 | Move to the previous/next heading (level 1–6) and read it. |

| Shift + F and F | Move to the previous/next form input and focus on it. |

| Shift + T and T | Move to the previous/next data table and focus on it. |

| Shift + B and B | Move to the previous/next button and read its label. |

| Shift + L and L | Move to the previous/next list and read its first list item. |

| Shift + I and I | Move to the previous/next list item and read it. |

| Enter/Return | (when link/button or other activatable item is selected) Activate item. |

| NVDA + Spacebar | (when form is selected) Enter form so individual items can be selected, or leave form if you are already in it. |

| Shift + Tab and Tab | (when inside form) Move between form inputs. |

| Up cursor and down cursor | (when inside form) Change form input values (in the case of controls like select boxes). |

| Spacebar | (when inside form) Select chosen value. |

| Ctrl + Alt + cursor keys | (when a table is selected) Move between table cells. |

Screen reader testing

Now you've gotten used to using a screen reader, we'd like you to use it to do some quick accessibility tests, to get an idea of how screen readers deal with good and bad webpage features:

- Look at good-semantics.html, and note how the headers are found by the screen reader and available to use for navigation. Now look at bad-semantics.html, and note how the screen reader gets none of this information. Imagine how annoying this would be when trying to navigate a really long page of text.

- Look at good-links.html, and note how they make sense when viewed out of context, for example in the VoiceOver Rotor. This is not the case with bad-links.html — they are all just "click here".

- Look at good-form.html, and note how the form inputs are described using their labels because we've added appropriate

<label>elements. In bad-form.html, they get an unhelpful label along the lines of "blank". - Look at our punk-bands-complete.html example, and see how the screen reader is able to associate columns and rows of content and read them out all together because we've defined the table headers properly. In bad-table.html, none of the cells can be associated at all. Note that NVDA seems to behave slightly strangely when you've only got a single table on a page; you could try WebAIM's table test page instead.

- Have a look at WAI-ARIA live regions example, and note how the screen reader will keep reading out the constantly updating section as it updates.

Other tooling

Screen readers are one of the most common types of assistive technology that you'll encounter as a web developer, but other AT types exist, and it is useful to be familiar with what users are potentially using to access your content. This section summarizes some of them.

Large text or braille keyboards

It is possible to get large text keyboards designed for use by visually impaired or older users, and braille keyboards designed to be usable by blind and severely visually impaired people.

Alternative pointing devices

When you think of pointing devices, mice are the obvious example, but there are other pointing devices designed to allow users with differing mobility impairments to navigate user interfaces more easily:

- Trackballs: Kind of like upside-down mice, trackballs consist of a mounted ball that stays stationary on your desk, which you can roll to move the pointer around. They are considered more precise and easier to handle than mice, especially for people with limited hand movement.

- Joysticks: A control stick that can be moved to move the pointer around. Joysticks are less precise than trackballs but usable by people with a wide range of physical impairments, even severe disabilities.

- Touchpads: Most modern laptops have a touchpad (sometimes called a trackpad) — a flat tactile sensor allowing you to move the pointer around with a finger, as well as performing multi-finger gestures in the same way as mobile gestures. You can buy external touchpads for devices that don't have internal ones. Some people find them to be more precise than mice.

Screen magnifiers

Screen magnifiers provide partially-sighted users with a magnified view of their device's display to enable them to understand and interact with device content more easily, as well as providing other features such as color adjustment to help with color blindness, and adjusting the size of mouse pointers and text cursors to make them easier to see.

Software and hardware screen magnifiers are available:

- Most modern operating systems have a built-in app for magnifying all or part of the screen, for example Zoom on mac or Magnifier on Windows. They also tend to provide options for universally increasing the text size, mouse cursor size, etc. Third-party options are available as well.

- Hardware screen magnifiers tend to consist of a separate screen that sits next to or in front of your device's screen and projects a larger version of it, or a zoomed version of part of it.

Voice recognition software

Voice (or speech) recognition software allows you to speak commands to control your device and/or speak the text of emails or documents and have the computer write the text for you. This is very useful for people who are unable to use a keyboard or other control mechanisms.

Modern operating systems have features built in to enable this (for example Dictation on mac, or Voice Access on Windows), and there are third-party apps available too, from desktop apps to browser extensions.

Switch controls

Switch controls provide a mechanism for interacting with devices for users with very limited mobility or cognitive impairment.

A switch control setup usually involves two parts:

- A physical switch or button for activating options on the device. You can also assign switch functionality to regular device buttons (such as volume controls) or keys on a keyboard.

- A device mode or third-party software add-on that makes the device compatible with the switch or button control. For example, Switch Access on Android is a mode whereby the different options in various situations (for example, apps on the home screen) are cycled through and then the one you want can be selected with a button or switch when reached.

Planning for accessibility

You should think carefully about accessibility near the start of each project. Make sure accessibility is considered during the initial design phase, so that you can:

- Get the basics right, for example using good document structure and providing alternative text for images.

- Carefully consider the best approach for features that are likely to have accessibility issues. For example, audio and video will definitely be inaccessible to some people, so you should provide alternatives such as transcripts and text tracks.

- Avoid costly mistakes later on. Issues uncovered near the end of a project tend to be far more time consuming and expensive to fix than issues caught early on.

User testing

You can't rely on automated tools alone for determining accessibility problems on your site. Every website project needs a user testing strategy, and it is highly recommended that you include some accessibility user groups:

- Try to get some screen reader users involved, some keyboard-only users, some non-hearing users, users with mobility impairments, etc.

- Get each group to try using the website generally, starting with looking at the home page and other major pages, and trying out some of the primary functionality. Typical examples include buying a product or making a booking. Ask them what their impressions were, and what problems they ran into.

- Next, get them to focus on features or workflows that you have specific accessibility concerns with, such as complex form controls or video players. Ask them what is lacking for them in terms of user experience, and what they'd like to see changed.

Some projects will have a budget to pay testing groups, whereas others will rely on unpaid volunteers or even colleagues and friends.

Accessibility testing checklist

The following list provides a checklist for you to follow to make sure you've carried out the recommended accessibility testing for your project:

- Make sure your HTML is as semantically correct as possible. Validating it is a good start, as is using an auditing tool.

- Check that your content makes sense when the CSS is turned off.

- Make sure your functionality is keyboard accessible (see Use semantic UI controls where possible for more details). Test using Tab, Return/Enter, etc.

- Make sure your non-text content has text alternatives. An auditing tool is good for catching such problems.

- Make sure your site's color contrast is acceptable, using a suitable checking tool.

- Make sure hidden content is visible by screen readers.

- Make sure that functionality is usable without JavaScript wherever possible.

- Use ARIA to improve accessibility where appropriate.

- Run your site through an auditing tool.

- Test it with a screen reader.

- Include an accessibility policy/statement somewhere findable on your site to say what you did.

Summary

Hopefully this article has given you an idea of the kinds of tools you can use to help fix accessibility issues, the assistive technology used by people with disabilities to help access the web.

In the next article we'll look how to write accessible HTML.